|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

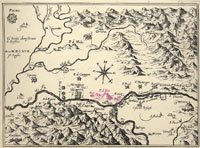

There in the place where the slopes of the Collio region lead gently down to the Isonzo River Valley, in a strip of land protected to the north by the Alps and open to the south to the warm currents of the Adriatic Sea, Celtic “clans” had already discovered a mild climate and hospitable nature in the seventh century B.C., and were transformed from fully-fledged nomads to settled agricultural farmers (man has always had the intuition to choose the best lands to plant his crops), while keeping however, their impetuous, combative and proud nature unchanged. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

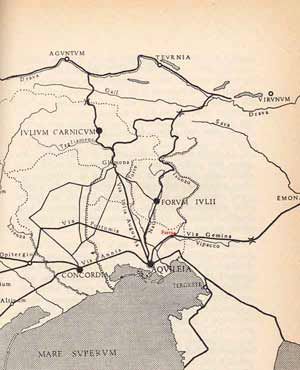

After the fourth century B.C., the intensification of trade with the North, the Hellenic Region and Magna Grecia left Farra d’Isonzo in a strategic position on these commercial routes; |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Farra d’Isonzo was quickly transformed into a communications centre, where different cultures interacted, creating the premises for the birth of a language (...Friulian!) as the glue for a special ethnic group that also desired a territorial identity. In 183 B.C., the condottiero Marco Claudio was able to consolidate Roman rule in Friuli, up to Aquileia (...an ancient town of Celtic origin called Akuleja, situated about 25 km south of Farra d’Isonzo), but was not able to establish neighbourly relations with the Celtic peoples that lived in the bordering territories. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In fact, in 52 B.C., the “Friulian” Celts, emerging from the forests and well-hidden valleys, struck the Roman army repeatedly in different points, winning a feat of great revenge by defeating the famed Tenth Legion, and reaching the walls of Aquileia, managing even to taunt Caesar himself, who was spending the winter in that city. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

On Mount Fortino (...the highest of the hills that surround Farra) a watchtower was immediately erected, so that the heights could be used to guard the adjacent Isonzo River Valley, over which a bridge was built, near the Mainizza (...an ancient district of Farra d’Isonzo) to connect them via Gemina and Julia Augusta. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ruins of an ancient Roman bridge on the Mainizza road | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

(Testifying to the respect for the Isonzo River, there still remains a votive altar dedicated to the river god “Aesontio” discovered near Mainizza). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. 2. Bas-relief sculptures depicting river gods, and 3. Aretta stone bearing a dedication to the god Aesontius discovered in Farra d'Isonzo near Mainizza |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In A.D. 238 the troops of Maximinius the Thracian, having reached Friuli from the far-off mists of the Pannonian Plain, found the road cut in two by a river with a violent flow: Maximinius thereupon began construction of a passage over the Isonzo with wooden casks requisitioned from the surrounding district. The invasions continued in the period from A.D. 401-408, with the arrival of Alaric’s Visigoths, who after crossing the Julian Alps, reached the Venetian Plain, dragging behind them Radagast’s Ostrogoth invasion, who forded the Isonzo near Mainizza (district of Farra d’Isonzo). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

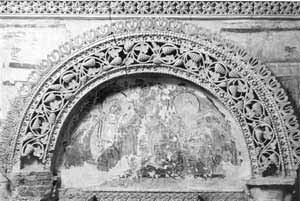

In A.D. 568, the Longobards arrived from their Pannonian settlements, led by King Albuin, having a great influence on Friulian history, customs and traditions. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Longobard Arches | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The particular story of the settlement of this people who came to mix with the Friulians can be understood only through careful study of clues found in documents, archaeological findings and place names. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

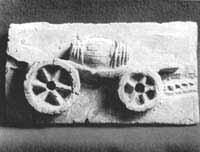

| Fragments discovered amongst the ruins of the Roman bridge in Farra d'Isonzo near Mainizza | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the Isontine Region, the place name Farra conserves one of the most characteristic testimonies of this period, in that the Longobard settlements were constituted by a family and military nucleus called “fara” (...one of the first knives of Lombard tradition was discovered in Farra d’Isonzo, on the slopes of Mount Fortino, and later defined the “Farra Model”). In addition, one often comes across the term “faramanni” in remains from this period, used to describe the free men of “fara”—men who were always ready to fight in the king’s service. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Given the numerous Longobard tombs discovered across the Friulian Plain, we might mention the necropolis found in the countryside around Farra d’Isonzo. For about two centuries (A.D. 568-776) Farra, like Friuli, enjoyed a period of great political, economic and cultural splendour. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Archaeological site at necropolis in Farra d'Isonzo and sepulchre | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

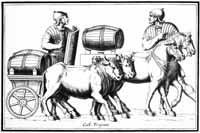

The first written testaments regarding Farra d’Isonzo are to be found in a document from A.D. 772, which contains a description of a donation by three brothers, Erfo, Anto and Marco (Lombard dukes of Friuli) of the territories of Farra d’Isonzo (...Farra juxta turrionem) to the Abbey of Sesto al Reghena. In the Berengar’s Imperial Diploma of 924 in the privilege of Otto I of 29 April 967, a “Castrum quod vocatur Farra” is cited. From the Abbey of Sesto al Reghena it became “Patrimonium ecclesiae aquileiensis” in 1031. With the decline of patriarchal sovereignty, new centres of power were created, and Farra became a possession of the County of Gorizia, and then of the Strassoldo family. Although the era was marked by a thousand vicissitudes, the wines of Farra d’Isonzo continued to be well-appreciated throughout Europe, from the Most Serene Republic of Venice to Hapsburg Emperor Charles V, from the Tsars of Russia to Vienna, capital of the empire of Austria, where horse-drawn wagons arrived regularly with great large casks from Farra. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The small town of Celtic origin was at the centre of Hungarian and Turkish invasions and suffered from the consequences of the Gradiscan Wars (1615-1617) as well as from the conflict between Venice and Austria, yet continued with its specialized cultivation of the grapes. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

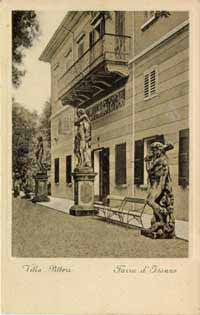

| In 1643, the Domenican friar Basilio Pica, former professor of Theology in Prague and Brno, arrived in Farra d’Isonzo as the guest of Count Richard Strassoldo, as did the aristocratic Pitteri family, who settled down here and built that magnificent structure, now destroyed, known once upon a time as Villa Pitteri, | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

where Giovanni Battista Pitteri (deputy to the parliament of Vienna) was born and his son Ferdinando (... podestà of Trieste for two legislatures), as well as and the poet Riccardo Pitteri |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

After the War of Gradisca during the 1600’s, there were no great events of international importance in Friuli, aside from the sordid diplomatic battle between Vienna and Venice... ....and the beginning of the history of the Bressan family... |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||